In 2014, the city of Los Angeles underwent a major transformation: a change in street lighting. LEDs have replaced neon lighting.

Hong Kong suffered a similar fate in 1995.

But what does this have to do with cinema?

The mood and atmosphere of a film is created by using images shot with special lighting, which gives the images a particular color and look, and a particular style to the film, reinforcing the anguish and mystery.

These neon lights made it possible to show the city's saturated sidewalks and colorful alleyways in an intimate way that has never been reproduced. Not only did they become an inseparable part of the film's universe, they also embellished the character of Hong Kong itself.

Ni le Los Angeles que nous voyons dans

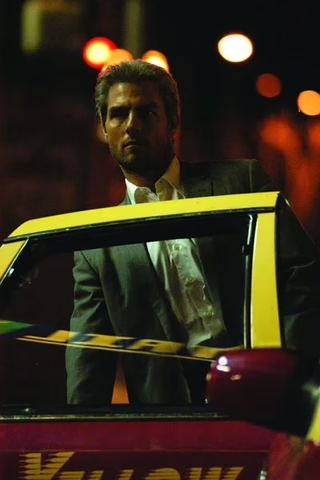

Neither the Los Angeles we see in

Collateral, nor the neon-soaked Hong Kong of Fallen Angels exist no more.

In the early days of cinema, the technology available at the time was not suited to shooting outside studios, especially at night, even with the help of trucks full of studio lighting. This period of history corresponds to the height of the popularity of incandescent street lamps, which were among the first forms of electric street lighting to be widely adopted in the United States. In a short space of time, their faint orange glow became an instantly recognizable feature of the urban landscape.

Relatively efficient and easy to maintain, incandescent lamps were deployed and while the main roads glowed, the alleys and side streets darkened and, as the lamps became scarcer in the poorer parts of town, crime and danger were ever present, lurking in the deep shadows between the luminaires.

These feelings of progress, modernity and danger lurking in dark corners have become cornerstones of film noir narrative and cinematography. Hitchcock's Shadow of a Doubt, one of the earliest film noirs, was one of the first to shoot at night on real city streets, and set the trend for location shooting.

Next came mercury vapor lamps. Much more efficient than traditional incandescent lamps and requiring less attention, they produced twice as much light per watt of electricity. However, instead of glowing with the same warm glow as incandescent lamps, mercury vapor lamps had a distinct blue-green hue that made them suitable for urban lighting.

Some initially complained about the cool tones, which tended to make skin pale and bloodless under their light. City streets were bright and widely lit for the first time, making them at least safer, although city centers saw a massive rise in crime rates that continued throughout the 1980s.

Following the energy crisis of 1973, which left the United States energy-deficient, the old sodium vapor lamps came back into fashion. With their characteristic orange lighting.

In 2009, the Los Angeles Bureau of Street Lighting began the process of converting the city's entire street lighting system from sodium and mercury vapor to

LEDs.

These new lamps not only produce more light and require much less maintenance than the most advanced sodium vapor lamps, they are also much more energy efficient. By 2016, Lais was already saving nearly $9 million a year thanks to reduced energy costs. This sum has only increased since then, as the price of these LED lamps dropped in the mid-2010s to match that of traditional street lighting.

By 2022, the Bureau of Street Lighting reported that 98% of Los Angeles' main and local roads had been converted to LEDs, while neon was slowly disappearing from the streets of Hong Kong.

However, in recent years, as Hong Kong has come increasingly under the sway of the Chinese state, this vision of the city has become increasingly fragile. The lure of LED lighting, which is cheaper and can burn up to five times more than neon, together with new laws imposing restrictions on outdoor signage, have accelerated the removal of neon throughout Hong Kong, while there were around 120,000 signs in Hong Kong in 2011, 1000 signs in Hong Kong in 2011, 11 years later this number had dropped to a staggering 400 as LEDs continue to replace the demand for new neon signs.

The Los Angeles Bureau of Street Lighting aimed for a color temperature of around 4,000 Kelvin, echoing what its research had discovered to be close to the color of moonlight, yet romantic in theory. 4,000 Kelvin on film and to the naked eye is surprisingly cool compared to the 2,200 Kelvin of sodium vapor lamps, which appear as an almost clinical cool white, the color temperature frequently chosen for hospital lighting. So it's not surprising that when a Californian city installed these LEDs on its streets, its citizens began affectionately referring to them as "prison lighting".

Within a year, the city council had adjusted their temperature to a much warmer 2700 Kelvin, closer to that of a domestic incandescent bulb.

LEDs' clarity and better color rendering can ironically make them more unreal than effectively monochromatic sodium vapor lamps. We've begun to get used to them, and some are even relieved. One filmmaker called sodium vapor the ugliest light known to cinematographers, but that doesn't stop filmmakers from constantly returning to the look of sodium and mercury vapor, frequently using gels and even changing fixtures to recapture some of the urban texture from a much more incandescent light than incandescent lamps. It's easy for most people to see the demise of something like neon as a tragedy, but I've been wondering for a while why changes to street lighting in the U.S. haven't received as much attention.

These values can be confusing, so go and clarify the notion of color temperature.